Update: I finally caved and moved my newsletter from TinyLetter to Substack.

Note: This post lives on my blog here. The charts are embedded over there, and are therefore interactive. The charts in this Substack newsletter are static images, but are hyperlinked to my source notebooks in case you want to go take a closer look.

This past year was many things, but one thing I’ve been thinking about is how it was the kind of year that will drive a lot of narrative in economic charts for years to come. Like 2009, the sharp peaks and steep valleys in income, spending, employment, money supply, and asset prices are a permanent reminder, etched in economic history: Some shit went down here.

I was barely a sentient human in 2009, wrapped up in various college dramas and only vaguely aware of the global chaos. But I paid attention this time. The thing that stood out to me was how…confusing…it felt. So many things came to a screeching halt, so many people were losing their jobs, yet the stock market was on a tear (except for a scary few weeks in March) and every e-commerce start-up I met was booming. As a venture investor trying to understand the current reality in order to make bets on the future, I thought I’d take a quick look at the year in the financial life of the U.S. consumer to try to make sense of it all.

There was the sharp shock in March, and then some modulation throughout the rest of 2020. But as a summary of the year (and, I should say, as an aggregate picture — there are of course huge income and wealth disparities):

People lost jobs, but wage losses were relatively minor. Government transfer payments more than made up for wage losses. As a result, personal disposable income was up.

People spent a bit more on goods, but way less on services, and less on interest payments thanks to interest rate decreases. Overall spending was somewhat down.

Higher income and lower spending meant people saved way more.

People paid down their credit cards, bought houses, and basically put the rest in cash. Net worth per capita grew.

Income

Private sector employment fell significantly in April, and hasn’t recovered fully. Twenty million jobs were lost at the peak of the crisis. Seven million still have not been regained.

Unsurprisingly, the leisure and hospitality industry suffered the most losses. During the first half of 2020, nearly half of leisure and hospitality workers lost their jobs. That industry is still 20% off of peak employment.

Leisure and hospitality is also the industry with the lowest hourly wages. The financial services industry, on the other hand, didn’t suffer much, and has among the highest wages.

So the way that math works out is that despite continued underemployment of the economy as a whole (7 million people are still out of a job, compared to pre-Covid!), aggregate employee compensation — that is, all dollars paid to all employees — is nearly back to pre-Covid levels, as you can see in the chart below.

Then add in the sheer size of transfer payments from government stimulus seen in the chart below…

…And disposable income actually saw a huge spike upwards, and is still elevated.

Spending

Everything more or less froze when Covid first turned into a global pandemic: Spending pulled back on goods, services, and energy. Food spending, though, spiked upwards (hoarding ftw!)

Food spending is still elevated as we’re all cooking at home more. Spending on services and energy, on the other hand, is still depressed as we can’t go to restaurants or travel…or do much of anything, really. The chart below shows the aggregate expenditures in four major categories.

Spending, after the brief pull-back, actually increased slightly on non-durable goods, and increased more up on durable goods, compared to pre-pandemic levels. Non-durable goods includes things like takeout, clothes, and gas. Durable goods includes things like cars, RVs, furniture, and Pelotons.

But because services spending is such a large category, depressed services spending means overall expenditures are still somewhat down.

People were able to spend less of their incomes on interest payments on credit cards and mortgages, as a result of loose monetary policy and interest rate declines. The chart below shows the drop in household debt payments as a percentage of income in 2020.

Overall, due to the increases in personal income and the decreases in outlays, the personal savings rate spiked up, and is still abnormally high compared to pretty stable pre-pandemic savings rates.

Assets and Liabilities

With all those savings, the amount of money held in currency, deposits, and money market funds by US households increased significantly (chart below, on the left). The value of households’ equity portfolios also increased over the year (chart below, on the right), for some of the reasons I talked about in this post, but people also bought equities with their extra savings…which then helped to further increase the price of equities.

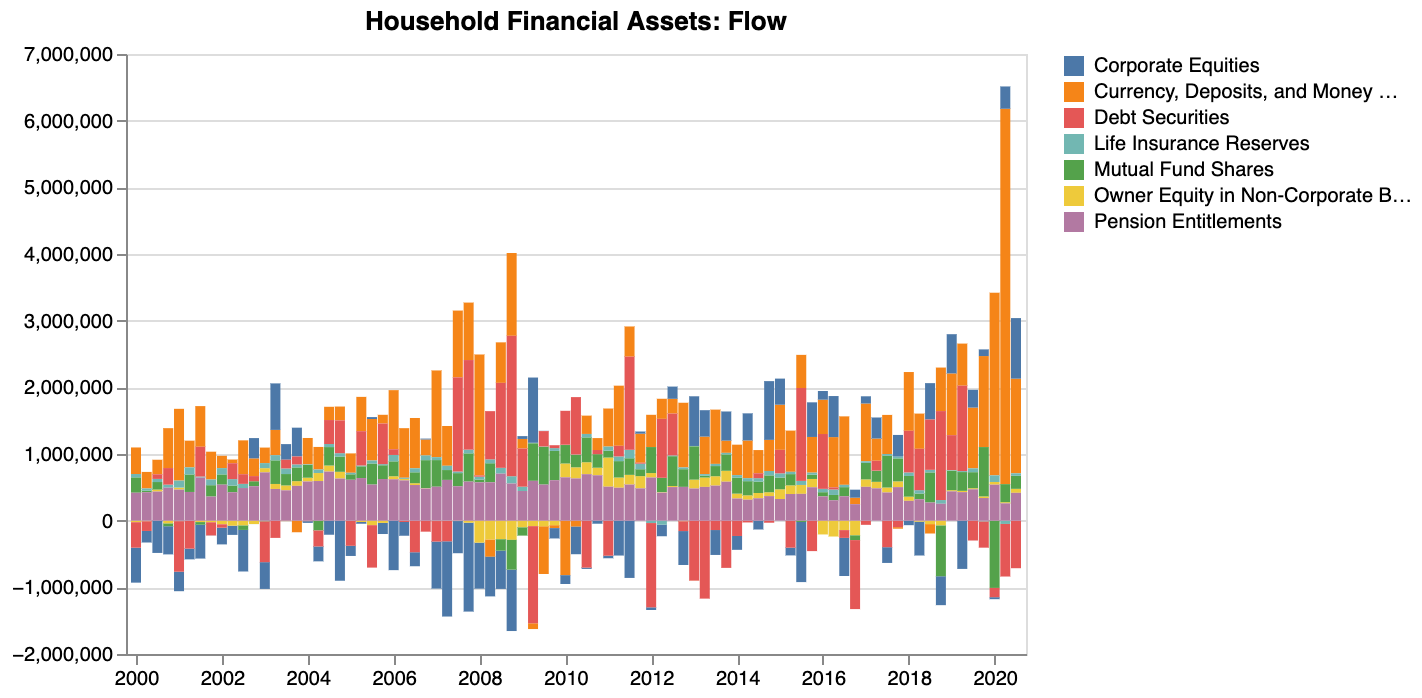

The chart below shows flows into and out of various asset classes. Currency, deposits and money market funds saw significant inflows throughout the year. Equities saw positive inflows as well, especially in the third quarter. (Fourth quarter data isn’t available yet.)

So overall, US household financial assets were up. The chart below shows the value of financial assets, by type of asset, held by US households.

Liabilities grew as well, but at a slower rate than assets. People paid down a lot of credit card debt, but took out even more in mortgages.

US household net worth, after the sharp asset dislocations that happened when the shock of Covid first hit, has climbed to exceed pre-Covid levels. In the chart below, the blue bars represent assets, the red bars represent liabilities, and the black line shows net worth (all in per capita terms).

On the non-financial assets front, people bought a lot of houses in 2020. That’s reflected in the increase in mortgage debt above. The chart below shows the homeownership rate spiked up from 65% to 68%.

Looking Ahead

It’s a confusing picture, and strangely rosy for all the human suffering that’s taken place. Millions are out of a job, but the aggregate consumer has more money in his or her pocket than before the pandemic. Thanks to government intervention, the impact wasn’t nearly as bad as it could’ve been, and all of the sharp dislocations in income and spending that did happen are, on the whole, modulating back to normal.

As a venture investor in 2021 focused on B2B software, I’ll continue to look for companies building B2B marketplaces, applications for the e-commerce and financial services verticals, and developer tools. Spending on goods is still elevated, even as the stimulus checks run out, and there’s more need than ever for efficient transactions run through centralized B2B marketplaces. E-commerce is, with retail stores intermittently closed, gaining market share even as the overall spending pie grows, and the industry needs flexible and modern tools. The dynamism and volatility in assets, mortgages, and debt is likely to get people more interested in, and engaged with, various financial services…and there’s plenty of room for improvement in our financial technology infrastructure. I’ll also continue to look for companies building tools to enable developers to become more efficient, as more and more of our economy becomes driven by technology and digital tools. None of these conclusions are exactly groundbreaking, but I now feel more comfortable about some of the fundamental macroeconomic factors at play.

And as a human person in 2021, I have to keep reminding myself that these averages and aggregates hide a lot of individual tragedies. I’ll continue to look for ways to help those less fortunate, and to try my best to rectify some of the ways in which our capitalistic system rewards and takes away unevenly and unfairly.